Flashback to 70s/80s, early in my career I realized that to be a good agriculturist I should also be forester and a rural sociologist as well. I lived in mountainous Central Visayas region where half of agriculture was conducted in the mountains. Kaingin and upland farming was rapidly evolving into a major environmental concern with mounting incidence of soil erosion and flooding issues, an aftermath of excessive logging of our forests in the period. The Central Visayas, Regional Development Council (RDC) launched a pilot project that aimed to model the way for decentralized decision making for forest and watershed care. I was part of this undertaking and eager to test an idea and learn as a younger professional!

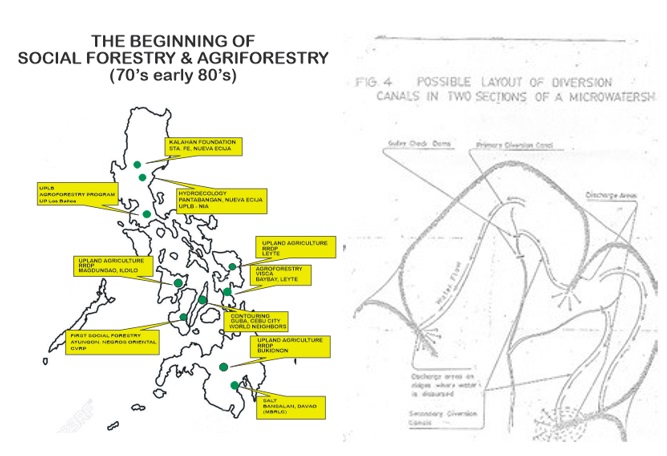

Ideas that inspired us (70’s/80’s)

- Farming in the mountains – a social issue first and foremost, before being a technical issue

- In the humid tropics, the nutrients are in the biomass, not in the soil

- Hilly land farming systems can be stabilized and made profitable

- Exit terraces and physical structures, enter biological methods of soil conservation

- Social forestry is a viable alternative to “command and control” (top down)

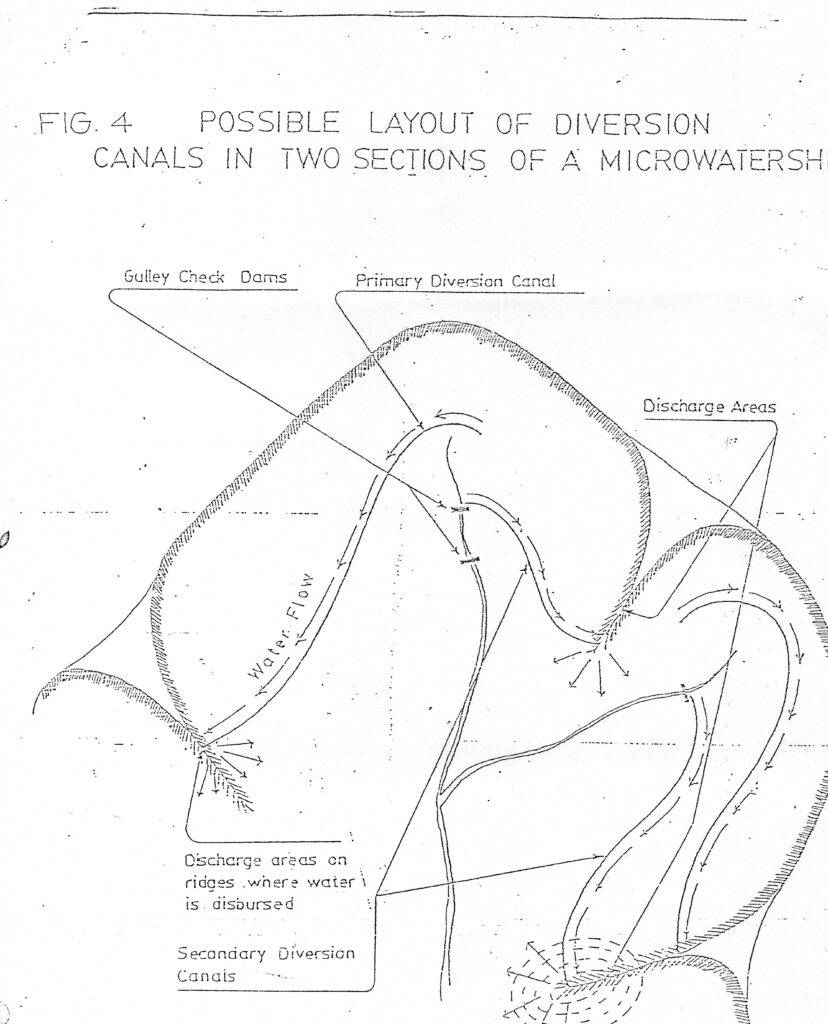

- For successful watershed management -start at the micro-watershed level

Remarkable Communities

Hilly communities in Alegria in Cebu, Barangay Magsaysay in Talibon, Bohol, Bayawan in Negros and Cangapa in Siquijor

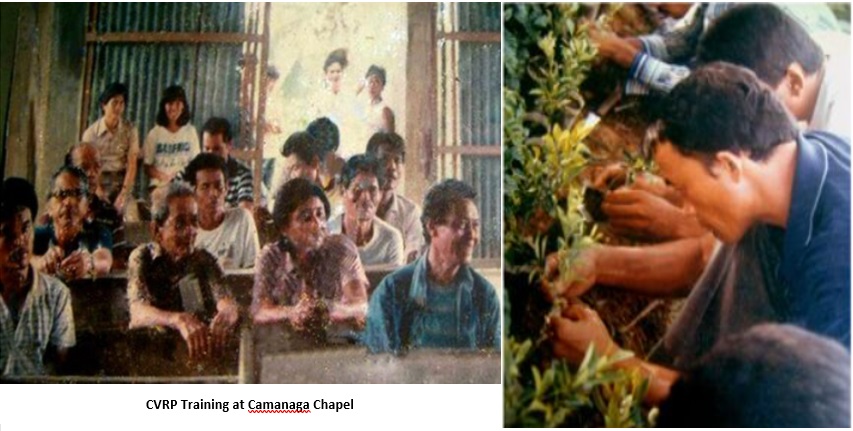

Catalytic projects that helped model the way

DOST PCARRD Technopack Project, WB-NEDA Central Visayas Regional Project; USAID DENR /DA Rainfed Resources Development Project.

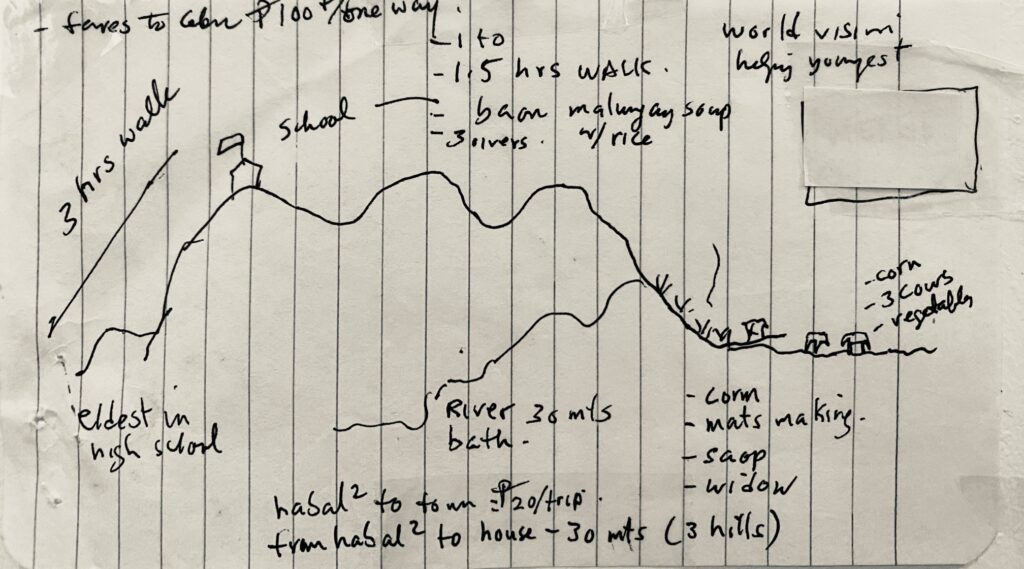

My field notes

Thought leaders, Mentors and Co-travelers

Two mentors stand out in this chapter of my technical life as part of the central Visayas experiment. Dr. Romy Raros (+) a likable maverick professor from Los Banos who was most creative on caffeine, nicotine and (a bit of) alcohol. His deep ideas on how nature works in the farm dislodged all of us from our comfort levels as professionals on viewing agriculture. And he also taught us the poor man’s agroforestry!

Another mentor who really shaped my technical paradigm is this Filipino American with who could fluently speak several dialects (tagalog, Bisaya, Tausug, chabacano) fluently with a broadcaster’s voice. The ladies swooned on him. Mr. Pat Dugan (+) brought with him the conscience of a “reformed” former logger. He credibly introduced us to the idea of community forestry (viable forest enterprise and sustainable protection.) These ideas eventually blossomed into the (albeit diluted) community forestry program we know of today in the Philippines (The earlier version as conceived by Pat was more daring and transformative). At least three DENR secretaries sought his ideas on CF.

A few other mentors helped shape my agro and forest paradigm. Dr. Percy Sajise (RRDP), and Pastor Delber Rice in Nueva Viscaysa who assured us that we were in the right direction from the socio – ecological standpoint! Mr. Bill Granert of the Soil and Water Conservation shaped our understanding of farmer-based soil and water conservation,

Dr. Fred Van De Vusse and Dr. Angel Alcala helped shape my coastal resources management understanding. Mr. Ver Zabala (+) (Ver), a very good friend had no equal in terms of understanding the farmers mind, and his passion and stamina to make agroforestry work on the ground. Mr. Rafael Jun Bojos taught me how to navigate the fisheries world

Mr. Rey Crsystal, the articulate Central Visayas NEDA regional director and Dr. Pons Batugal (DOST PCARRD) helped me in many ways on how to bring science to influence policy and politics. I cannot mention my other esteemed peers and younger co travelers, lest I do injustice if I miss any name, each an important player in, my book.

Insights

- The upland issues were a lot simpler then. One of the key major issues then was kaingin. Today it is already about commodity driven agriculture (e.g., yellow corn in hilly lands).

- Notwithstanding its gaps, the Central Visayas experiment in the 80s was the germ of a concept of transforming government from an ineffective regulator to one fostering people-oriented resource management.

- The acid test of a cost effectiveness of good upland technology would be labor intensity. If too labor intensive, it won’t last or it won’t spread well (e.g., SALT).

- Market forces are more powerful than the best technologies and extension work.

- Policy-based incentive and systems (not project incentives) coupled with context-based regulations is really the key in the uplands.

- This was my first my first full exposure the” institutional culture” of DA and DENR, and LGU. These cultures either enabled or constrained meaningful development…

- Too much money in so short a project timeframe is a recipe for non-sustainability of successful, project inspired practices.

Acknowledgements: community pictures and CVRP picture – Ms. Charito Chiu CVRP

Leave a reply